Making Conflict Transformational: Step #5 – Understand Your Approach to Conflict

Imagine with me the following conflict situations, noticing how people approach conflict differently.

Ian and Chelsea have been married for two years. The honeymoon stage is over and they’re starting to notice some significant differences in the way they do life. Chelsea is super organized and loves to plan everything while Ian prefers to let life just happen. They’re repeatedly bumping up against this difference in their planning styles. Chelsea would like to work out a compromise while Ian is adamant that his way is the best way. His favorite response when Chelsea is worked up about his lack of planning is, “Just chill, Chelsea, just chill.”

Jacob and Sam have been friends for years. Jacob is more outwardly assertive and typically dictates what they end up doing. Sam doesn’t necessarily like having limited say in what they do, but he feels it’s important to keep the peace. When he has brought it up, Sam has denied that there is any conflict. And besides, Jacob’s ideas are usually pretty good and they end up having a good time.

Emily and Madison are church friends. They’re both married and have young children. Their children often get together for play dates. They’ve recently experienced conflict over their different parenting styles. Emily is stricter and sometimes tries to push rules onto Madison’s kids that Madison doesn’t believe are all that important. They’ve decided to talk about the tension and explore the values and other factors beneath each person’s parenting style. They’re committed to finding a solution that honors what’s good in both approaches and are prepared to compromise a bit, if necessary.

As you can see from these examples, there are different ways of approaching conflict. Allan Simpson and Darrin Hotte, in their Workbook for Engaging Conflict, describe five approaches to conflict: avoid, assert, accommodate, compromise, and cooperate.

Conflict Approaches

The first approach to conflict is to simply avoid it. People who avoid conflict are typically uncooperative and non-assertive. In the conflict scenarios I posed, Sam is an avoider. When Jacob brings up the tension, he simply dismisses Jacob’s observations as irrelevant. Conflict? What conflict? Avoiders are not looking out for their interests or the interests of others. They’re oblivious to conflict, minimize it so that it doesn’t seem important, or skirt around it because they don’t want to deal with it. Now, to be fair, sometimes the best approach to certain kinds of conflict is to avoid it. The conflict might be inconsequential, the timing might not be right to dive into the conflict, engaging with the conflict might make matters worse, or other factors might make avoidance the best strategy in the moment.

The second approach is to assert oneself in keeping with one’s own interests. Ian, in the first example, appears to follow this approach when he insists that his relaxed approach to planning is the best way, end of discussion. Again, this approach is not always bad. There are times when we need to be more forceful and stand up for our preferences.

The opposite of the asserting approach would be to accommodate. With this approach, the person’s primary interest is keeping the peace and so is willing to give up their own interests for the sake of the other. Sam would be an example of an accommodator. He doesn’t want to create waves with Jacob and so he often keeps quiet when he disagrees with his friend. This kind of approach has biblical support in passages like Philippians 2:3-4: “…Rather, in humility value others above yourselves, not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others.” Shouldn’t we be willing to give up our interests for others? Of course, we should. Yet, sometimes our acquiescence can perpetuate dysfunctional relational dynamics. It may be important for us to stand up for ourselves or stand against something that is inappropriate.

The fourth approach is compromise. Here, both parties in the conflict are prepared to let go of some of their interests for the sake of the other. It’s a give and take kind of an approach. Emily and Madison are willing to make some compromises in their parenting styles (at least, when they’re together), so that their children can continue to play with one another. However, they’re actually holding out for something more, which brings us to the final approach to conflict.

The Cooperate approach is all about trying to find a mutually satisfying solution that allows both parties to retain what is most important to them. Now, in the real world, this often requires some compromise. However, the starting point for cooperators is to explore conflict resolutions that honor both their position and the position of the other person. Emily and Madison are hoping for this as they discuss parenting styles and the values and beliefs that guide those practices. Of course, this quest for a win-win solution often requires a certain amount of assertiveness (e.g. expressing views), accommodation (e.g. recognizing that some of my preferences are less important and negotiable), avoidance (focusing on what’s most important at the current stage of the conflict and ignoring other tensions – at least for the time being), and compromise (giving up some things to gain others).

Conflict Responses

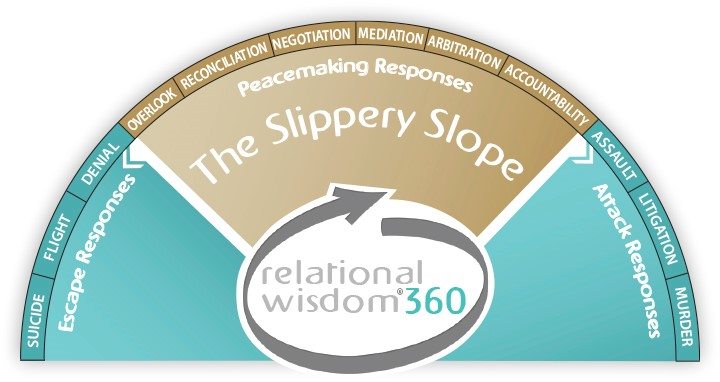

What are some examples of conflict responses that emerge from these approaches? Ken Sande, in his book The Peacemaker, describes what he calls the Slippery Slope of conflict responses (see diagram below). He lays out three categories of conflict responses. On the one end of the Slippery Slope spectrum, you have escape responses while attack responses occupy the other end. In the middle, between these unhealthy responses is the peacemaking set of responses. Let’s take a look at the specific responses in each of these sets.

Escape Responses

The escape responses include denial, flight and the most tragic escape response, suicide. With denial, the individual pretends there’s no problem. When someone flees a conflict situation, they may do so in the moment by removing themselves from the people with whom they are in conflict or they can actually try to flee the situation permanently. Examples of these kinds of flight responses could be ending a friendship, divorce, quitting a job, or leaving a church. In some situations, the person may feel like their only alternative is the ultimate in escape tactics, suicide. All these responses stem from a deeply held aversion to conflict, which causes them to avoid it at all costs. All three of these are examples of how avoiders from the five conflict approaches we looked at earlier might respond to conflict when avoidance is taken to unhealthy extremes.

Attack Responses

Asserters, who are most concerned about their own interests, will sometimes adopt attack responses to conflict (which are at the other end of the Slippery Slope spectrum). This could involve physical or verbal assault where they try to use force or intimidation to overwhelm their opponent. They may resort to litigation where they bring the matter to a civil judge for a decision. In some cases, asserters will even resort to murder, either in their hearts or physically. Of course, as mentioned earlier, not all assertiveness is bad; it just needs to be used appropriately.

Peacemaking Responses

Thankfully, several healthy peacemaking responses stand between these sets of escape and attack responses. These responses feature a varying mixture of all five conflict approaches we looked at earlier: avoid, assert, accommodate, compromise, and cooperate.

So, let’s start on the escape or accommodation side of the conflict response spectrum. The first response is to overlook. Proverbs 19:11 says, “A person’s wisdom yields patience; it is to one’s glory to overlook an offense.” So, we know that there are times when the best peacemaking response is to simply ignore what the other person has done. It could be a minor, one-time offense. It could be part of something bigger and more complex that requires us to overlook it because of the larger issues at stake.

The second peacemaking strategy is reconciliation. According to Sande, this involves discussion, loving confrontation, and confession. There is enough self-awareness and assertiveness so that one or both parties can admit their fault in the situation.

Another peacemaking strategy is negotiation. This is a type of bargaining process, which often involves money, property, or other rights. In organizations, leaders will often engage in negotiations around various departmental or ministry interests.

Mediation, as a peacemaking response, enlists the help of a third party who attempts to guide the disputants to a good resolution.

Sometimes, both parties in a conflict cannot come to a resolution and agree to binding arbitration, which gives an arbitrator the authority to decide on a resolution pathway.

Sande also mentions a conflict response that he calls, “accountability.” From a Christian perspective, this one features church leaders holding someone to account for their sinful behavior. Likely, the conflict has gotten so bad that others must intervene to hopefully bring about a healthy resolution.

We’ve looked at five approaches to conflict and twelve possible conflict response. At different points, I’ve hinted that underlying factors influence our default approaches and responses to conflict. Of course, situational dynamics might also influence how we respond. Once again, I’m indebted to Simpson and Hotte for their work on these influence factors.

Influence Factors

Our cultural background can have a profound influence on how we respond in conflict situations. This certainly includes ethnicity, which is typically what we think of when we hear the word “culture.” However, it also involves gender, age, geography, associations, and subcultures within each. Culture often contributes significantly to the building of values, viewpoints, and behavioral patterns, which constantly influence the way we react in certain situations.

Of course, our family of origin also influences our conflict responses. How did your family deal with conflict? What were the unspoken “rules of engagement?” What was acceptable, even exemplary, behavior? What was unacceptable? These conflict engagement patterns, reinforced over time, create well-worn behavioral pathways that are easy for us to follow throughout adulthood.

Thinking about the conflict situation itself, the personalities involved will also influence our response. For example, some people are more likely to be aggressive if the other person has a loud, abrasive kind of personality. The nature of the relationships obviously affects how we respond, as well. We’ll likely respond differently if the other person is a family member or if they’re a co-worker or neighbor.

The approach the other person adopts will often influence our reactions, too. Are they defending themselves or are they willing to learn about us and the situation from our perspective? Are they accusing or is their curiosity about what might really be happening that is beyond their current understanding? We often take cues from the other person’s tone of voice and body language as to how they’re approaching the conflict, and we respond accordingly.

Of course, the nature of the conflict itself influences our responses. Low-impact conflict requires a very different response than stubborn conflict as we saw in the blog, “Making Conflict Transformational: Step #2 – Identify the Type of Conflict and the Intensity Factors.”

Simpson and Hotte also maintain that the context of the conflict influences people’s responses. Is it a private or public setting? Are there longstanding issues embedded in the conflict or does it relate to a more transient tension?

Power differences can also impact our conflict responses. For example, when one party in the conflict has more knowledge about the issue, say finances, it can give them more sway in the situation. Someone who is very articulate may also have more power in a tense conversation. Whether we have more power or less affects how we respond.

Time restraints can also play into how we act when faced with conflict. One or both disputants may have another pressing commitment, which can either expedite or stall the conflict conversation. When we try to resolve conflict too quickly, we may cut important relational builders like active listening and affirmation that are an important part of a healthy conflict resolution process.

In this blog, we’ve looked at several approaches and corresponding responses to conflict. We’ve explored some of the internal and external factors that can influence how we respond. Understanding our approach to conflict and some of the influence factors is important for at least two reasons. First, understanding the factors that push us to respond in certain ways can actually empower us to challenge those forces and minimize their influence. Exposing them to the light of our awareness can rob them of their indiscriminate influence in our lives. Second, we can reinforce or implant other factors that give rise to healthier responses. This often requires us to learn new ways of thinking and responding in conflict situations and to have others hold us accountable to respond better. Admittedly, this process takes time and tenacity as old conflict management habits die hard.

Now, that we have looked at how people typically approach conflict and the factors that might influence their responses, we’ll look at how we can build pathways of peace in the next blog.

Blogs in the Making Conflict Transformational Series:

Overview of the Six Steps to Making Conflict Transformational

Step #1 - Recognize that Conflict is Necessary

Step #2 - Identify the Type of Conflict and Intensity Factors

Step #3 - Pray Through the Conflict

Step #4 - Check Your Own Heart

Step #5 - Understand Your Approach to Conflict

Step #6 - Build Pathways of Peace

Dr. Randy Wollf is Associate Professor of Practical Theology and Leadership Studies at MB Seminary (part of ACTS Seminaries of Trinity Western University) and Director of MinistryLift. Randy has also served as a pastor, church planter, and missionary.